The Code-first approach

- To understand this better, let's compare:

- What tools do software teams use?

- What tools do creative teams use?

- What tools do mechanical teams use?

- Code-first

We think you deserve better tools that don't have arbitrary restraints and the best way to give you these tools is with a Code-first approach. It's a departure from convention for sure, but the upsides can't be ignored.

Imagine kids playing at two different houses. In the first house, the kids are given toy shovels, buckets and similar, but are told strictly they can only use them in the sand pit. This might be fun enough, but at the other house, kids are given power tools and no restrictions on where they can play. Imagine the fun and mischief the second set of kids would have!

Parental responsibility aside, the first house describes the situation of mechanical teams currently. The tools they're provided for hardware design are good and fun, but being limited to the sandbox, that is the proprietary formats, the difficulty in accessing their designs programmatically and the GUIs themselves are ultimately limiting.

The origin story for KittyCAD is that a software engineer asked for CAD advice from a mechanical engineer (Jessie Frazelle & Jordan Noone respectively) because she quickly hit limits with the tools she had been using1.

It's telling that a software engineer so quickly found problems with a genre of tool she had only recently started using, as there is a particular perspective software folk bring to building and managing complex systems. To be clear the issue she found were less related to modelling geometry, instead to do with process and automation that's possible (or not) with these tools.

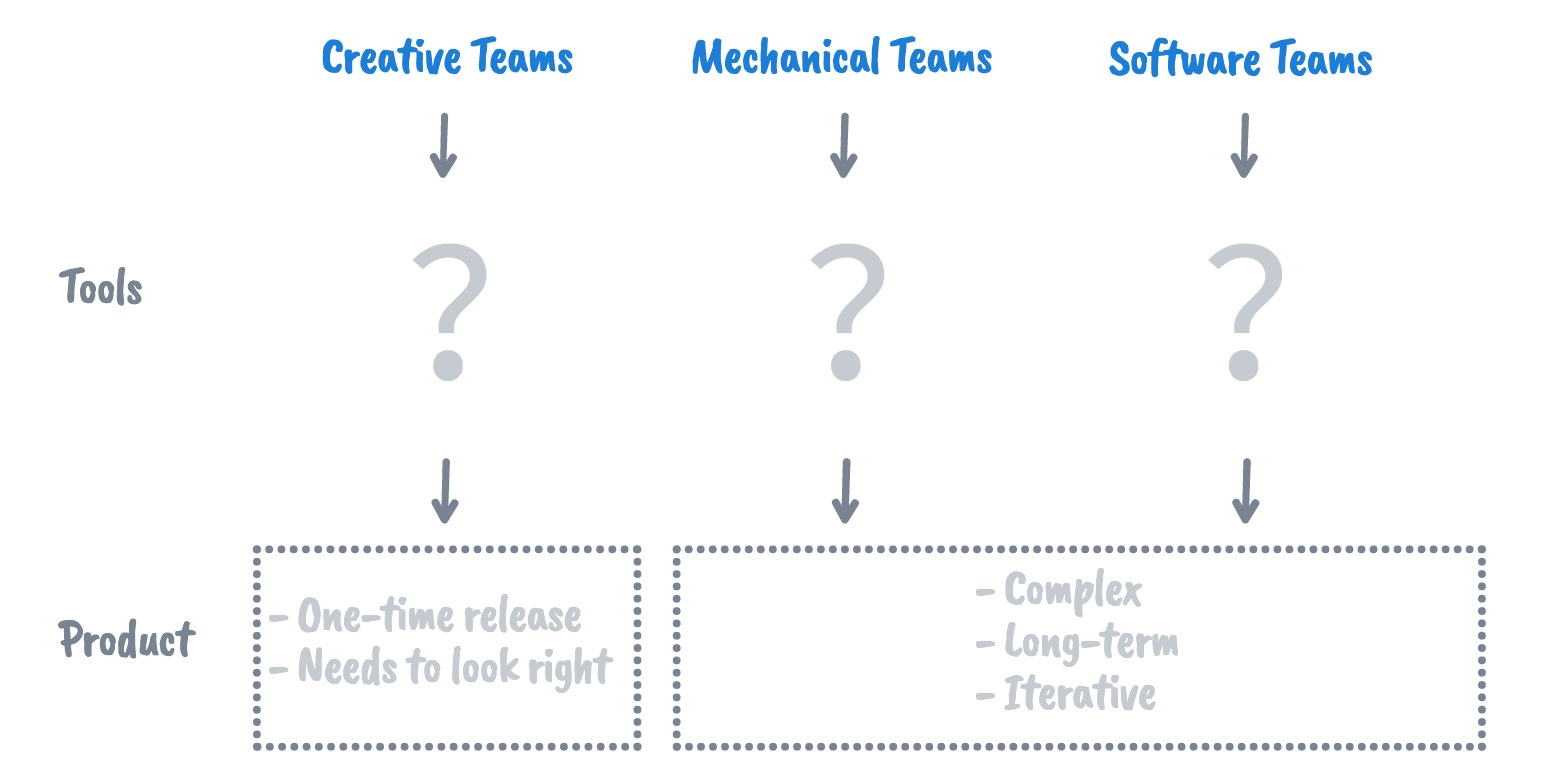

To understand this better, let's compare:

On a high level, the products mechanical and software teams build are similar:

- They both work on very complex products, A mechanical product and a software application are both made up of hundreds or thousands of parts that need to interact with one another, in which a single flawed part or function can bring the design/app to its knees.

- The products are often long-term, needing to last years and be updated throughout.

- Building on the last point, the products are updated, built up and improved through an iterative process.

In contrast, imagine a short animated film produced by a creative team. Their product is a one-time release, normally doesn't need to be supported after the fact and it only needs to "look right". A couple of minor mistakes in the background will not meaningfully affect the final product. The film might be complex, but it's a very different situation when it's not a long-term project that needs to be iterated on further.

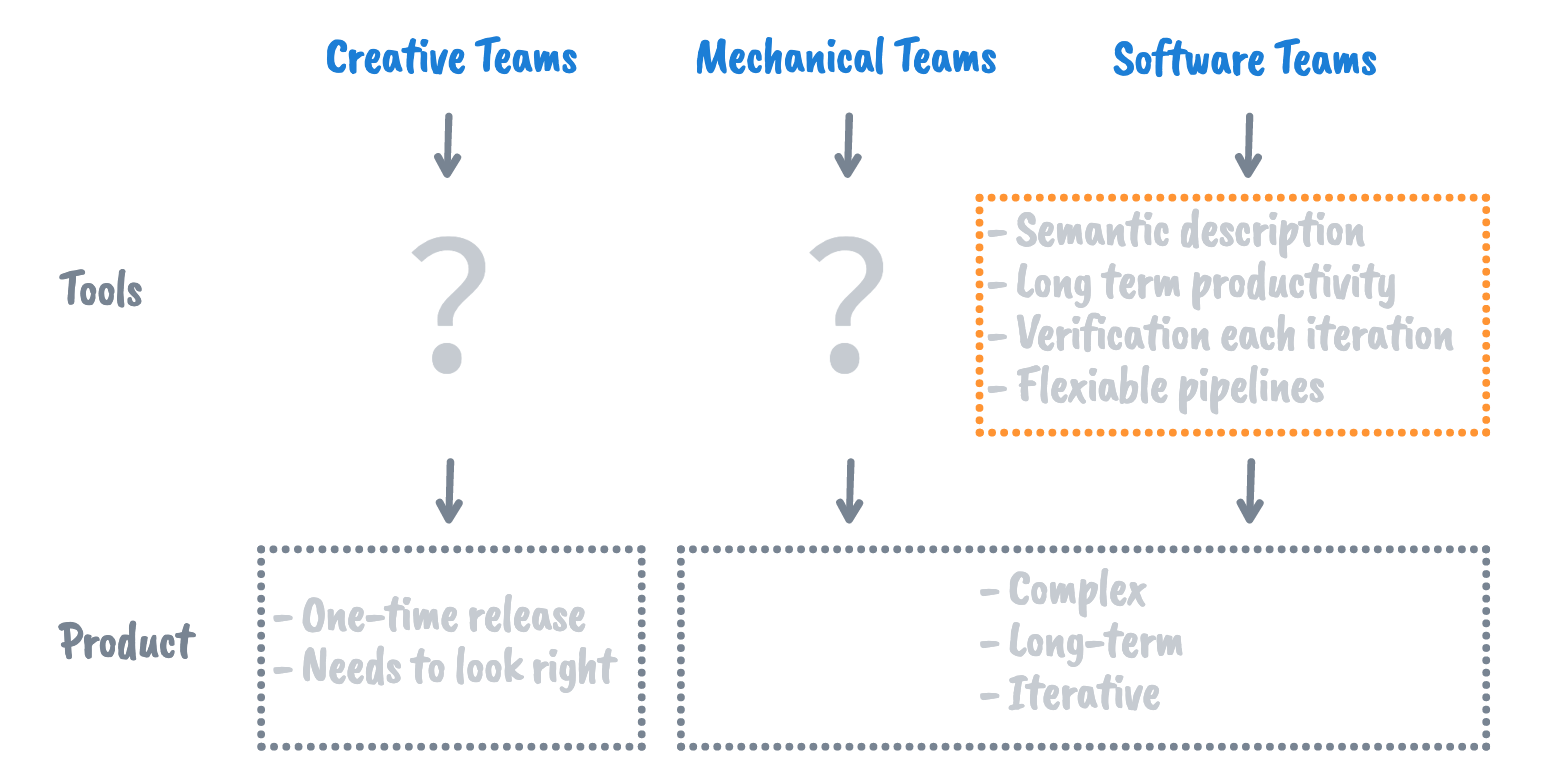

What tools do software teams use?

Software teams live and breathe automation, it's their job, and code is their tool. Code or software also happens to be their product, but because it's a tool, software teams can write code for their development process, leveraging the same skillset for their own workflow efficiency.

- Semantic description: Because the product is code and therefore consists entirely of human-readable text, the product retains a semantic description of itself. Given the complexity of their product, the semantic description is of utter importance as it allows any engineer, to jump into new parts of the code and start contributing.

- Long-term productivity: These teams use industry-standard version control and collaboration tools2. Allowing them to make surgical changes even as the product increases in complexity.

- Verification each iteration: Software teams use automated tests to verify changes have not introduced unintended flaws, giving confidence when making changes. This also removes the overhead of determining what needs to be manually verified before the software is released again. A mechanical equivalent would be FEM automatically run when changes are made and warning their team if stress increases from the last run.

- Flexible pipelines: No single software team or product is the same, therefore pipelines that can be tailored to any use case are needed, and this plays into the previously mentioned point that code is a tool as well as the final product. Pipeline here means an automation task, typical examples are formatting code, running the "verification each iteration" tests, and deploying the code to a production environment. Looking at this from a mechanical perspective, verification tests are more likely to take the form of simulations, but could also factor in manufacturing processes3. Producing artifacts like drawings, 3d models, and a BOM are also good examples.

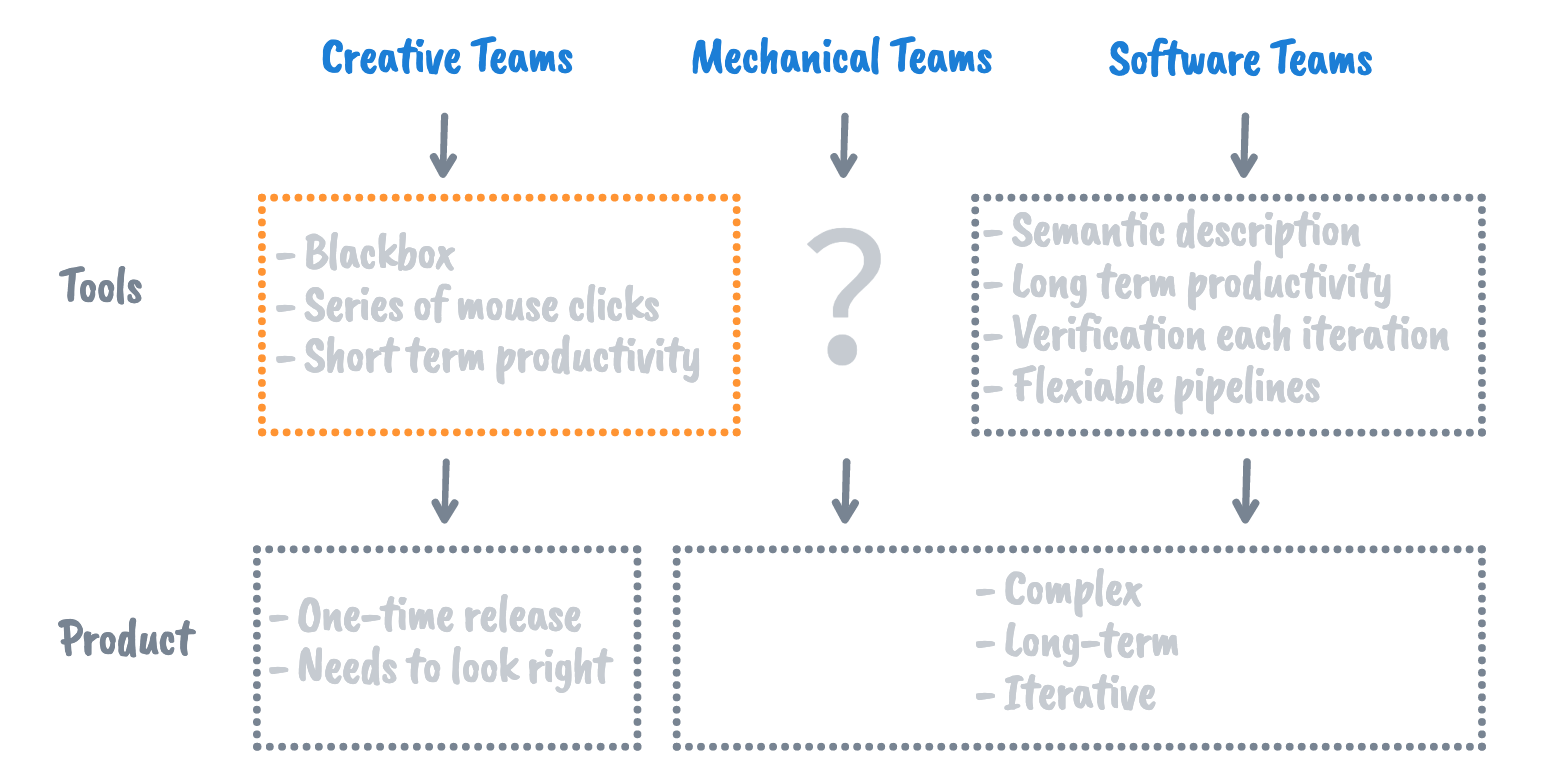

Let's compare this to Creative teams.

What tools do creative teams use?

Creative Teams use tools that prioritize creative expression and producing content. This is achieved with intuitive GUIs4. Because each part of their product is built up from a series of mouse clicks, and then saved in an opaque proprietary format there is no semantic description of the product and version control becomes harder5. Making edits after the fact is at the whims of the GUI. Sometimes edits work, but geometry breaking is also common. These tools prioritise short-term productivity over long, as this suits the use-case of a one-time release product.

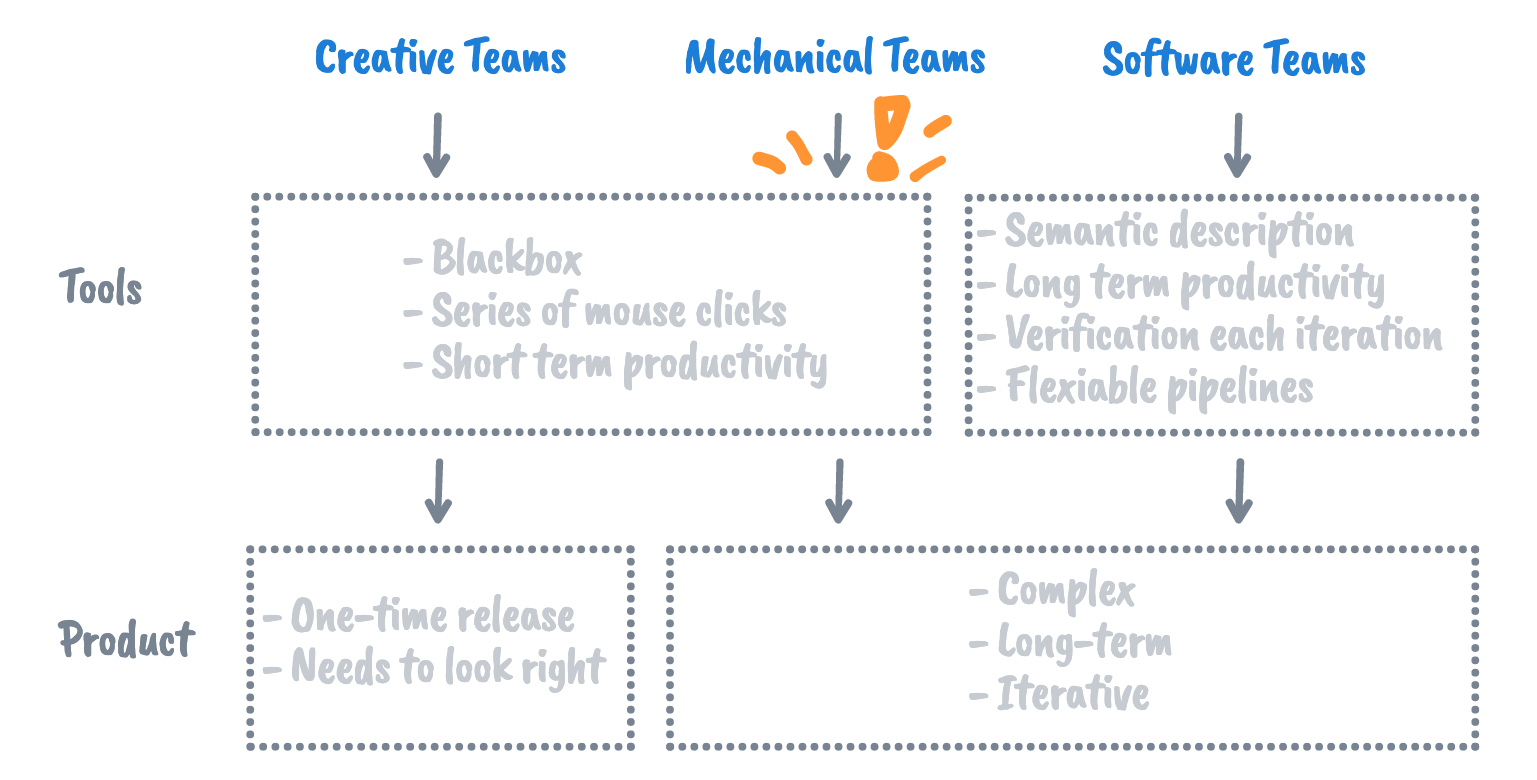

Finally, let's look at the mechanical team.

What tools do mechanical teams use?

You probably saw this coming. I'm proposing that the tools provided to mechanical teams today are not suitable for the type of product they are building. It's not that the tools are bad, but more so that it's the wrong paradigm.

Code-first

Am I really proposing that mechanical teams write software instead standard-industry CAD GUIs?

Yes and no. "Yes" because the amount of rework that's normal for a mechanical team is staggering! Battling with breaking geometry when editing, de-featuring and meshing a part again for FEM because there was a small change, re-creating drawings or re-running renders. All this and more can be handled by automated pipelines.

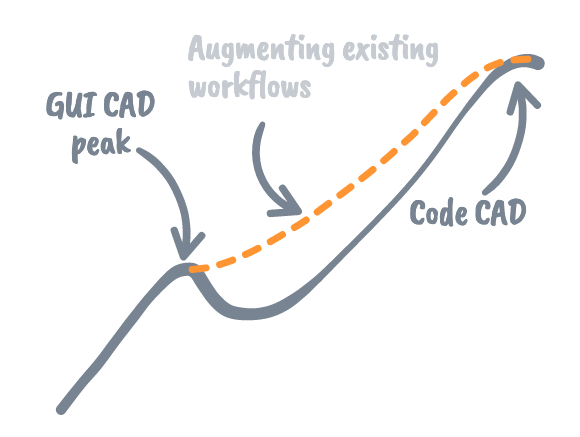

"No" because most teams won't swap outright to a code-first approach. Instead, KittyCAD is aiming to provide tools to allow mechanical teams to augment their current workflow, automating the onerous tasks first and adding more with time.

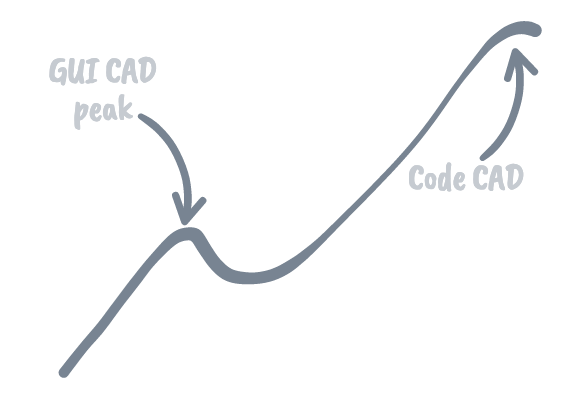

Still hesitant? That's understandable, after all, it's a new paradigm, I think the right approach is to give it 5 minutes. Because a Code-first approach naturally requires ramp-up time here's how adoption might play out.

Making a hard swap to Code-first naturally results in a dip in productivity, as the team needs to learn the new tools and workflows, but pays off in the long run.

However, by incrementally automating tasks in an existing workflow, we can get efficiency gains immediately. That's why KittyCAD is focusing on tools for existing files. Converting them, pulling out metadata about their geometry and calculating properties like volume, surface area, etc. Then much more beyond that, take a look at our roadmap for what's planned.

I know I'd rather play outside the sand pit with big-kid tools, and I'm incredibly excited to see more mechanical teams have access to code as a new tool in their tool-belt and what they'll be able to do with it.

Footnotes

-

Jessie Frazelle has written an excellent break down: Mechanical CAD: Yesterday, Today, and Tomorrow. ↩

-

Git is almost universally used for version control. Online collaboration tools based on git (Github, GitLab, BitBucket) are also very common. ↩

-

A simple example might be checking the minimum internal radius of a machined part is equal to or greater than the minimum tool radius. ↩

-

Graphical User Interface. ↩

-

There are proprietary solutions to version control bundled with some CAD software, or Git can be used with any file type. However, both cases are still worse than version control with human-readable formats (contains semantic description), as git with text formats not only gives a history of what files changed and when, but a breakdown of the changes per-line with comments from the author about the changes. ↩